The Unfeathered Bird

Katrina van Grouw

Princeton University Press, 2013

The first thing you notice about this book is the alert and watchful attitude of the male Indian Peafowl (or peacock) on the dust jacket. He is dark and jagged, dangerous looking and has a full set of ghostly display feathers that make his head come off the page in your direction. He is staring at you with no eyes. He is, after all, a skeleton and the threat he poses is more of a dare. He seems to ask, “Do you have the nerve to see what’s inside? It might change your appreciation of your beloved birds. And change is always risky.”

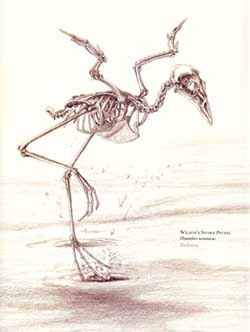

The skill to create this masterful drawing along with the intelligence and nerve to use it in such an important place are indicative of the high level of work and unfettered creativity to be found inside. The drawings reveal detail and shape so well you feel you should be able to pick up the bones and rotate them for better understanding. Even more impressive is the way artist/author van Grouw manages to get a drawing of a skeleton to impart something of the behavior of the bird. Or maybe, by revealing such detail of form, she is demonstrating the way structure and behavior are linked, influencing each other in an eternal dance of changes. This might be one of the reasons the book exists at all.

In fact, she says just that in the introduction, but not until after she rushes to reassure the squeamish that there are no “guts or gizzards” included in the book. While this is technically accurate, there is a gray area where you could accuse her of transgressing the spirit of the statement. The “ick” response is generally triggered by the presence of soft tissue, especially if it looks wet or slimy. You will find windpipes (tracheae), tongues, voice boxes (syrinxes or syringes) and muscles in some of the drawings. Probably the worst offender is the Trumpet Manucode (p. 278, a bird-of-paradise) with its “extraordinary coiled windpipe” which may well be taken for a pile of intestines were it not for the neatness of the coil. Thus, the extremely sensitive reader might be bothered by this breach. To her credit, however, van Grouw made these soft parts as dry as the bones, but still just as alive. Her treatment is well within the spirit of her promise.

Her second disclaimer, that there is “no biochemistry and very little physiology” is completely accurate. I did, however, have to crack open my Webster’s 11th to be sure of that. It would indeed be difficult to cover much biochemistry or physiology without the organs, tissues and cells, a.k.a. “guts and gizzards” dispensed with in the first disclaimer. So, having fenced off these two big areas of anatomy from our fragile senses, what remains? Morphology – and the book has it in spades.

The organization of the material in the book is as logical as it is delightfully unorthodox. Rather than covering the various aspects of avian structure in modern taxonomic order she reaches back to “the first truly scientific classification of the natural world – the Systema Naturae of Linnaeus”. What her book has in common with that one is a concern with outward appearances and the structures which form them. She invokes the concept of convergent evolution as an explanation of the underlying logic. It serves well. However, if you are disturbed by this heresy, try to remember this is ostensibly an art book. It just happens to have a more than generous helping of clear, understandable text to help you comprehend what is in the drawings.

The book is divided into two uneven parts. The small first part uses more familiar species, to Europeans at least, to demonstrate and explain the basic structures common to all birds. Van Grouw is thorough but doesn’t belabor the point she is making. As an example, there are six drawings revealing the left leg and foot of a Mallard covering two adjacent pages (pp. 16-17). The text describes how the leg fits together and how it articulates, but it is all in plain English, with little reliance on technical nomenclature. She does call a “thigh bone” a femur, but a hip is still a hip and a knee is a knee. She wants you to understand the basic structure so when you look at the leg of another bird, a Southern Screamer for example, you see the same parts, but also the differences – that is, after all, the point of the book. She isn’t trying to bury you in information. To prove my point (and belabor it a bit), she describes the scaly, unfeathered part of a bird’s legs and feet, but did not once use the term podotheca.

The second, and by far the larger part of the book, describes anatomical structures found in birds with shared behaviors or niches and therefore, similar adaptations. Obviously, there isn’t room for treatment of every species with a shared feature, so van Grouw describes the basic elements using a single species. Then she brings in descriptions of variations on that theme using both image and text. When you have finished reading the section and looking at the drawings you haven’t learned how to differentiate a Mallard from a scoter, but you know they are as different as they are similar. You can pick up an incredible cache of information if you want it, but that isn’t a requirement for enjoying the book.

Perhaps the one feature that distinguishes this collection of bird drawings from others is van Grouw’s ability to show how all these bones relate to each other in a live bird. Each skeleton exudes the nature – personality if you will allow it – of the species it is. You can feel the weight of a heavy bird like the Maribou Stork (p. 176); likewise the lack of it in the White-throated Hummingbird (p. 81). The Common Black-headed Gull (p. 151) has its bill open, its neck a little extended, and its wings a bit out and down. You can almost hear it complaining. The same is true for the Jackass Penguin (pp. 112-113) only its upside-down head is tucked under its belly as if it were braying at something low and behind it. These are very believable, active poses you are not going to find elsewhere.

Van Grouw’s sense of humor adds to the mix, too. High on the list in this category is a skeleton Budgerigar (p. 57) perched on a dowel, not a branch, looking at itself in a mirror with an attached bell. I won’t try to explain it. It’s too deep and too funny all at the same time. There is also a Eurasian Sparrowhawk (p. 40), no feathers, with a Eurasian Collared Dove in its talons – caption: “Feathers removed and feathers being removed.” Priceless!

Finally, the book ends with European Robin (p. 282) – dare I say “Cock Robin” – and he (it) is most assuredly dead. As dead, in fact, as all the others are alive. It’s as though van Grouw intended to accentuate the lack of life in this drawing just to point out how much of it there is on the preceding pages. The point was well made. All that remains is the index, but even there a Mallard is laughing at you to begin it and showing you its backside to end it. You get the feeling he’d stick out his tongue if he had one. It would be easy to dismiss this work as “just another coffee table book” if you didn’t look at anything but its size and shape. And certainly, it would serve well in that capacity, but there is much more to this volume than some pretty pictures and some words nobody will care to read. There is a synergy of element and effort in this work that produced a volume I will treasure for a long, long time.

To Katrina van Grouw, I say bravo. And thank you. Now, get to work on the one with guts and gizzards. I can hardly wait.